Welcome to art Snacks, a newsletter serving bite-sized art history morsels to hungry adults.

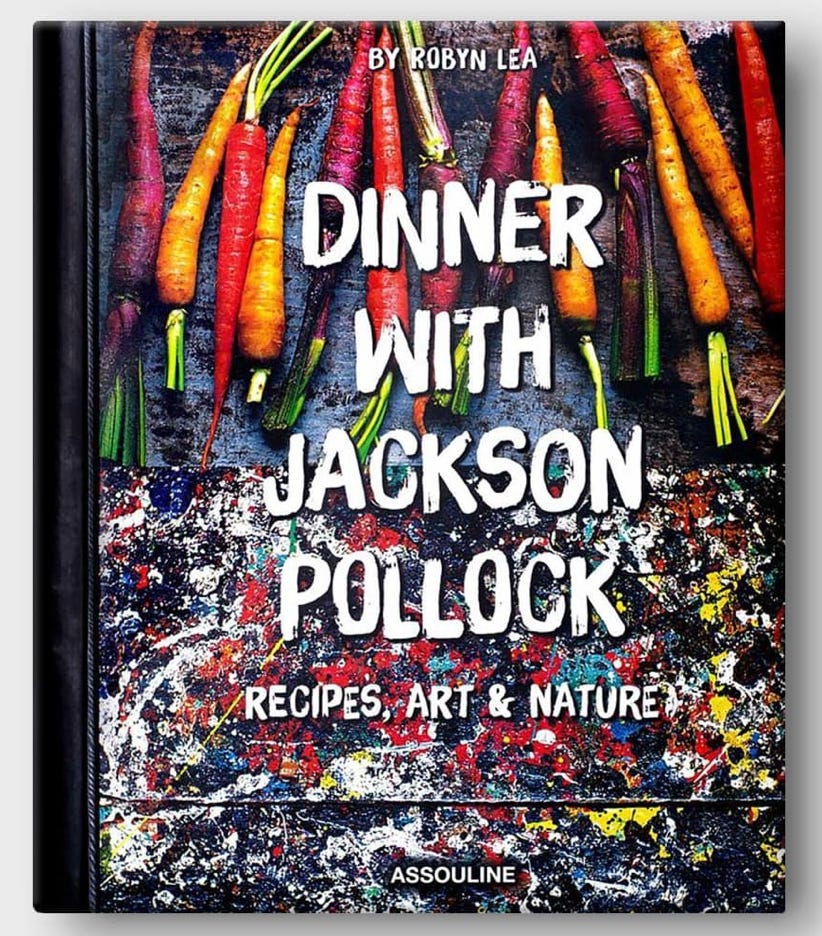

After spending most of my twenties eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner with plastic utensils at my desk on Wall Street, the simple act of cooking—with actual groceries I bought myself (!)—in my own kitchen feels like a small, victorious luxury. This Memorial Day weekend, I’m planning to make this Creamy Lobster Stew from Dinner with Jackson Pollock (Assouline), which I’ll serve with a butter lettuce and chive salad. I’ll probably be sipping a glass of rosé and watching Sirens on Netflix while I cook—because what better way to kick off the long weekend than with a soapy, dark comedy set on an East Coast beach estate, starring Meghann Fahy?

The cookbook was a gift from my dear friend Max M. back in those Wall Street analyst days. At the time, it sat untouched in my cramped Upper East Side galley kitchen like some beautiful, exotic artifact. But since moving to California, I’ve been able to crack it open—a lot—something for which I feel great gratitude.

My delight in the domestic—the thrill of the farmer’s market hunt, setting a beautiful table—however, is layered with complexity. For generations of women before me, the kitchen wasn’t a place of leisure or creative freedom; it was a symbol of confinement.

In the 1970s, pioneering performance and video artists like Martha Rosler used their work to challenge the gender norms and domestic expectations placed on women. Rosler examined the household labor women were expected to perform (work that was often invisible and for which they did not get much credit), alongside the language and broader cultural symbols that enshrined those expectations.

In Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975, a 6-minute grainy black-and-white video, Rosler takes the leading role—that of a cooking show host—and presents the viewer with an alphabetical schema of kitchen utensils. From within her own tight NYC kitchen, Rosler holds up a series of objects for the camera, which she names: apron (she ties it on), bowl (she mimes stirring something in it), chopper (she whacks the bottom of the bowl with a mean-looking knife).

What starts as a calm, albeit mechanical, demonstration becomes increasingly unhinged as Rosler progresses through the alphabet. By ‘S’ she’s simulating digging a grave with a spoon, and by ‘T’ she’s tenderizing all the other utensils on her work surface. Thereafter, Rosler gives up on presenting objects altogether, instead making violent arm gestures to outline the remainder of the alphabet.

Semiotics of the Kitchen is a parody of 1960s and 70s cooking shows like Julia Child’s The French Chef. However, where Child brought charm, competence, and warmth to her show, Rosler brings coldness and aggression. Rosler’s automaton-like movements remind me of a wind-up doll on the verge of malfunction or a Stepford wife short-circuiting.

Semiotics is the systematic study of sign process and the communication of meaning. In Rosler’s words, “an anti-Julia Child replaces the domesticated 'meaning' of tools with a lexicon of rage and frustration.” She goes on to say, “when the woman speaks, she names her own oppression.” Whereas any given Julia Child show is narratively coherent—she walks through the various steps to make a beef bourguignon, let’s say—Rosler’s demonstration, systematized into alpha order, becomes inherently incoherent. It seems unlikely that anything could actually be cooked in this way. This erosion of meaning mirrors the mindless nature (and loss of life-meaning) experienced when forced to repeat mundane, domestic chores.

In the 1970s, video art was primarily distributed via (VHS and) U-matic tapes, a then-cutting-edge cassette format. These tapes were shared (often mailed back and forth) through a network of noncommercial distribution centers such as Electronic Arts Intermix and The Kitchen in New York, which helped circulate works to museums, universities, and artist-run spaces. Museums (the Whitney and MOMA were early adopters) began acquiring video art in this format, marking a shift in how time-based media was exhibited and preserved. Rosler has said she’s happy that Semiotics now resides permanently on YouTube, hugely amplifying its reach.

I watched the video from beginning to end a few times—perhaps as a mental warm-up for my imminent holiday weekend cooking spree. I encourage you to do the same.

Martha Rosler has an extensive body of work across photography, video and performance. Her photomontage series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–72) juxtaposed images of American domestic tranquility with horrifying images from the Vietnam War (“the living room war”) to devastating effect. Check out Beauty Rest, First Lady Nixon and Boys Room (all from the series).

You can see more work, like The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974-1975, at her website here. This short video is Rosler in her own words.

If you find yourself out east this summer, consider a visit to the former home of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in Springs, NY—where both the cooking and the action painting took place. The house is largely preserved as it was at the time of Krasner’s death in 1984, offering a rare glimpse into the artists’ domestic and creative lives.

Have a fun and restful Memorial Day Weekend! 🦞

Thanks for this. Have always love the Martha Rosler piece. Did not know about the Pollock cookbook. Wow!