Welcome to art Snacks, a newsletter serving bite-sized art history morsels to hungry adults.

Hello! Today we’re going to talk about the mother of performance art, Marina Abramović! I’m splitting this snack into two letters. Here we’ll cover her seminal early work Rhythm 0, 1974 (a genre-defining performance where objects (including a gun) were laid on a table and the audience was invited to use them at will, upon Abramović) and The Lovers, 1988, a 90-day piece where Abramović and her partner and artistic collaborator, Ulay, walked 2,000 km towards one another across the Great Wall of China to meet in the middle and formally end their relationship.

Some background. Last Thanksgiving, I visited the Royal Academy of Arts in London where a major retrospective on Abramović was underway. The show surveyed more than 50 years of her work. Given the ephemeral nature of performance art, the pieces were either shown via video footage or performed by artists trained in her method, following her ‘instructions’ for each work. I participated in 3 live performances, two of which I shall discuss.

For readers on my personal email list, the section covering Rhythm 0 may be familiar. If so, feel free to jump down directly to The Lovers. For the rest of you, buckle up. You’re in for a treat!

When I read that the mother of performance art, Marina Abramović, was (in 2023!) the first woman to have an exhibition within the main galleries in the 250-year history of the Royal Academy of Arts, I was shocked. For those unfamiliar with the RA, it is one of London’s major arts institutions, situated in Burlington House on Picadilly, in the bustling heart of Mayfair. Originally a private residence, the building became the home of the RA at its founding in 1768.

I’ve been to the RA countless times—most memorably dragged by my parents at 3 am in March 1999 for our timed entry to the Monet in the 20th Century show (I was so sleepy!). But I am embarrassed to say the lack of female representation never occurred to me. Last November, as I crossed the cobbled courtyard, my family in tow, I wondered… was this really the RA’s first full-blown show by a female artist?

Sadly, yes. Of the 38 founding members of the RA, only two—Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser—were women. But despite their founding member status, these female founders were swiftly marginalized from the scene (both literally and figuratively!). As you can see in Zoffany’s chromatic portrait, The Academicians, while the male academicians lounge about man-spreading, Angelica and Mary have been relegated to mere representations. Their membership is recorded derivatively, via the portraits hanging high up on the wall.

Not only were Kauffman and Moser excluded from the life drawing room (we are now 100 years past Gentileschi’s death and nothing has changed!) but also from important Academy meetings as well. Zoffany’s portrait pretty accurately sums up the relative positioning of male and female artists at the time (male = artist, producer; female = subject, pretty picture). But as time went on, things got worse. Post Kauffmann and Moser, no female artist was allowed full membership to the RA until 1936. And it was only in 2023, that the RA (which has annual blockbuster retrospectives) had its first major solo exhibition by a female artist: Marina Abramović.

Abramović was born in 1946 and grew up in post-war Yugoslavia, the daughter of high-ranking socialist officials. She trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in both Belgrade and Zagreb, but in the 1970s her practice suddenly and dramatically evolved away from painting.

“One day I saw twelve military planes passing by, and they made this incredible drawing in the sky. The lines appeared and disappeared, and then there was blue sky again. It was like a revelation… Why did I have to use something two-dimensional when I had freedom to use anything I wanted? I could use fire and water and the body and sound.”

Shortly thereafter, Abramović stopped painting and started experimenting with real-time works using her body as the canvas. Rhythm 0, from 1974, is one of her earliest but most iconic works of this, then nascent, genre.

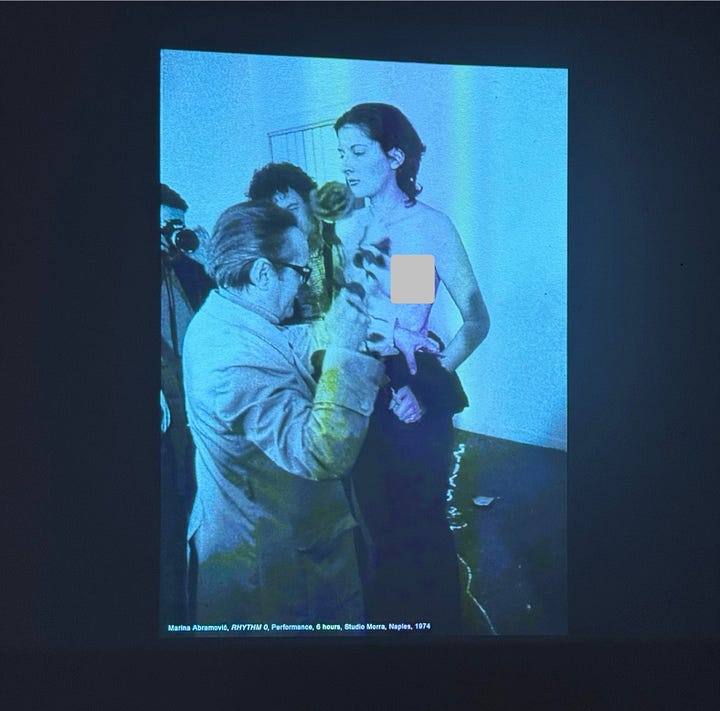

Originally performed in Naples in 1974, in Rhythm 0 Abramović laid an altar-like table with 72 items. Some were pleasant: feathers, chocolate cake, wine, a newspaper, others—scissors, a gun and bullet, knives, an axe—less so. Abramović stood next to the table for 6 hours alongside instructions for the audience as follows: “There are 72 objects on the table that one can use upon me as desired. I am the object. During this period I take full responsibility.”

While the performance started benignly, a few hours in the audience turned violent. People slashed her skin, stripped her to her waist, laughed. Someone held the gun to her clavicle. Other audience members had to intervene (grabbing the gun, throwing the bullet out of the window) to ensure her safety. Behind the table at the RA there was incriminating video footage of the performance where we see tears welling in Abramović's eyes. Abramović has since recounted that she noticed that while the perpetrators were mostly men, the women were the ones whispering instructions.

When the performance ended and Abramović finally moved to leave the gallery, the public fled. They were frightened of her now she had agency again. When she returned to her hotel, she looked in the mirror. She saw something new: strands of white hair. The effects of the trauma of the experience.

The idea of audience-as-artist where the audience’s emotions are reflected onto Abramović-the-canvas, is fascinating. The viewer has choices and it’s interesting to see what choices they make within the constraints of a gallery or the pressure of herd mentality. In one performance of Rhythm 5, 1974 (where Abramović lay down inside a five-pointed star of fire) she passed out from the fumes. Some in the audience stepped inside the star and removed her to safety. I’m sure they wondered if they’d be ousted from the gallery for interrupting the performance but yet they did what they felt they had to do.

In Imponderabilia, 1977/2023, performed during our visit to the RA, visitors were invited to make a similar choice. Two naked people stood facing each other in a narrow doorway with a small gap between them. An RA docent gestured for visitors to walk between them to get to the next gallery. The gap was tiny, the passage awkward and potentially rather uncomfortable for the performers. My husband walked between them, relaxed and seemingly unperturbed. I, however, found a side door and bypassed the whole situation via that. I don’t think what I did was a cop-out. It was my choice of how to interact/not interact with piece, a choice as viable as walking between them. (It was also a choice taken by many GenZ visitors, I have since read.)

On November 30, 1975, during a performance of Lips of Thomas, Abramović met Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen). Their meeting was perhaps fated. Towards the end of Abramović’s performance (which entailed her cutting her stomach with a razor blade), Ulay approached her and started to care for her wounds, an unusual act on the part of an audience member. The performance was on Abramović’s birthday and after it was over, she offered to take people out for a drink. Ulay suggested he also treat everyone to a drink as well, given it was his birthday too. Abramović didn’t believe him and asked for proof. Ulay retrieved his diary from which the page ‘30th November’ had been torn out. Abramović was astonished. Her diary was missing the same page.

What followed was an intense period of romantic and creative collaboration. Abramović and Ulay outlined an ART VITAL manifesto—rules by which they’d live and create, together as artists. The manifesto’s staccato mantras included: ‘no fixed living place,’ ‘mobile energy,’ ‘extended vulnerability’ and importantly, ‘no predicted end.’ The manifesto was radical. Abramović and Ulay decamped into a mobile home, and what followed was 12 years of collaborative performances. Seminal works included AAA-AAA, 1978 (where they continuously screamed into one another’s faces, see video above) and Nightsea Crossing (a series of 22 performances around the world, where Ulay and Abramović sat silent and motionless, fasting, at either end of a table facing each other, usually for 9 hours at a stretch).

For many years, Abramović and Ulay had planned and petitioned the Chinese government for permission to create a piece involving the Great Wall of China. They’d originally discussed walking along the wall and getting married in the middle, but by the time their petition was granted, their relationship had almost entirely dissolved. So, in a final symphonic performance, The Lovers, 1988, Abramović and Ulay set out from separate ends of the wall and walked over 2,00km towards one another. Their meeting point was the place at which it all ended.

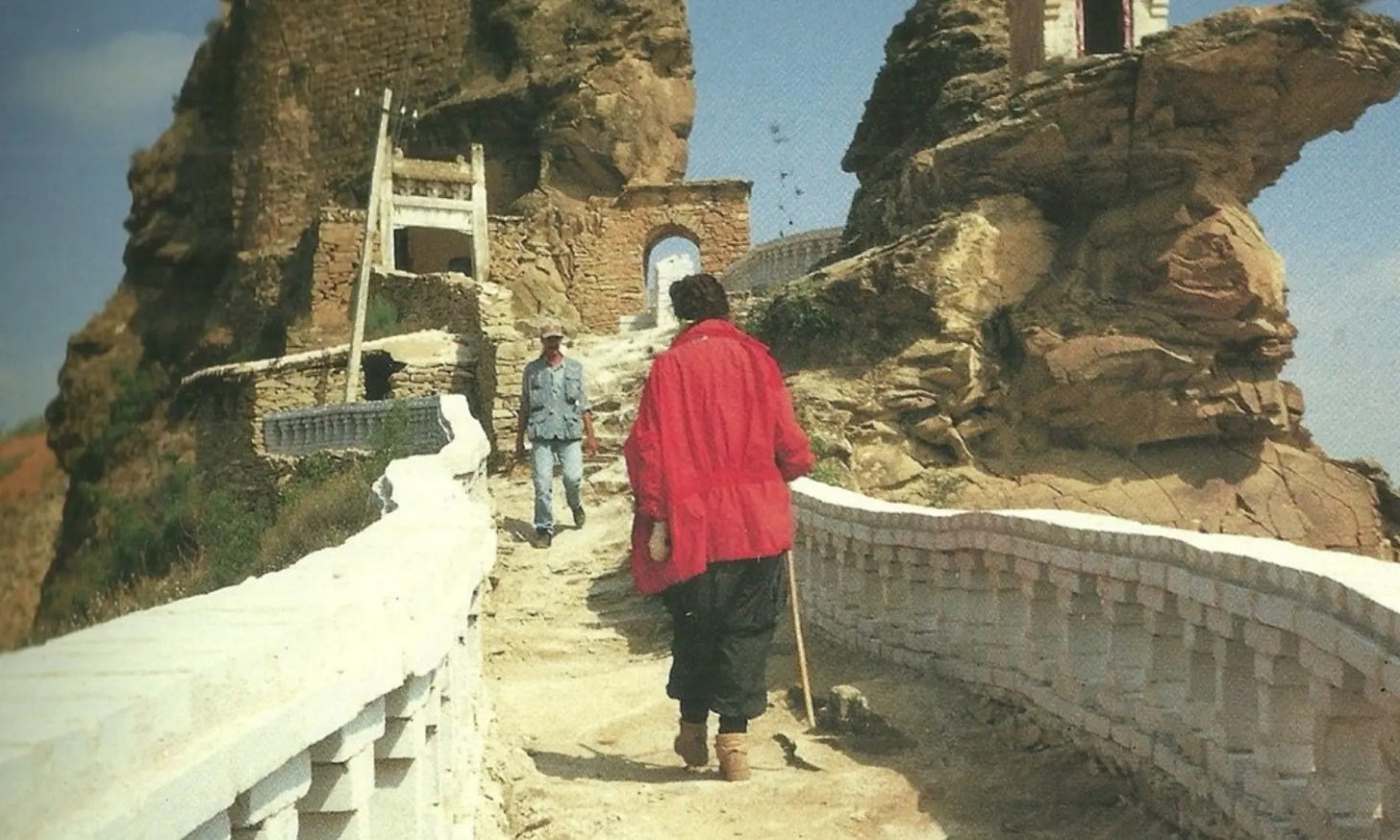

The Great Wall of China is often compared to a dragon: its head is in the East, buried in the Yellow Sea, its tail lying in the Gobi Desert in the West and its body the mountains. Abramović started from the sea and Ulay from the desert. The performance took 90 days. They walked an average of 20km per day, across sandy plains, and mountains, through precarious snowy ridges where the wall had long fallen away, and did so without communicating. When they finally met, in the middle of the wall, they said goodbye and parted ways. They did not speak for the next 22 years.

Let’s fast-forward to 2009/2010. Abramović was putting on a retrospective at MOMA, where she performed The Artist is Present. Her performance instructions were to sit in a chair at a table every day for 3 months for the duration of the museum’s opening hours. An empty chair was placed opposite Abramović and members of the public were invited to sit down and commune silently with her, without touching. One day, without prior warning and among a throng of visitors, Ulay sat down in the chair. It was the first time Abramovich had seen him in over two decades. In a moment where art directly intersected with life, Abramovich broke the rules of her own performance for the very first time. With tears in her eyes, she reached over to him, to hold his hand. I will rarely ask you to actively click a link out of here, but watching this moment (also below) is certainly worth it.

Part II on Marina Abramović will be covered in the next newsletter.