Welcome to art Snacks, a newsletter serving bite-sized art history morsels to hungry adults.

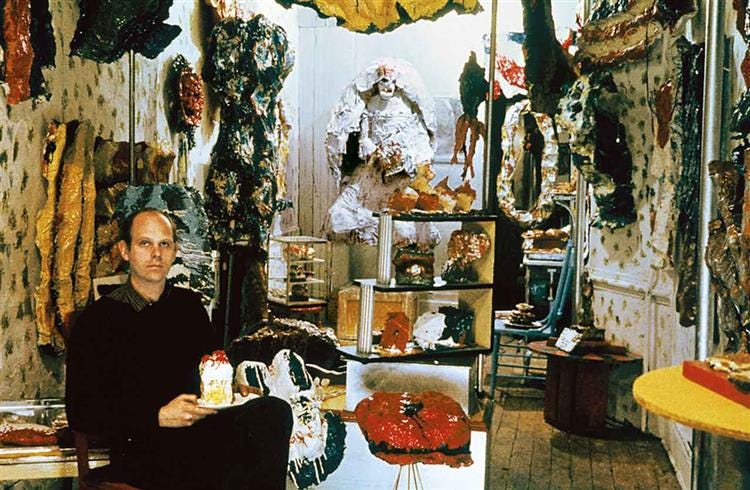

It’s the winter of 1961, and you’re wandering the gritty streets of New York’s East Village. The air smells faintly of grease and trash and cigarettes, and the storefronts alternate between pawn shops and bodegas. But one shop window draws you in. Inside, oversized ice cream cones slump beside sagging underwear, plaster pies balance precariously on shelves, and a man in paint-splattered clothes chats casually with a customer. This is not a store—it’s The Store. And the man—Claes Oldenburg—is inviting you into a chaotic, absurd, and strangely familiar world where art and commerce collide.

While Allan Kaprow was directing his Happenings in a loft just a few blocks away—inviting participants to squeeze orange juice and tonelessly recite random words in the name of art—his peer Oldenburg was staging a different kind of disruption. The Store wasn’t a performance in the traditional sense, but it pulsed with theatricality: a hybrid of studio, gallery, and sidewalk sale that reimagined what art could be and where it could reside.

Certain pieces stood out among the riot of plaster and chickenwire that filled The Store. Sagging ice cream sundaes with thick, impastoed surfaces seemed less like treats and more like melting monuments to indulgence. Nearby, Braselette (1961) hung awkwardly, its lumpy, distorted shape turning a delicate garment into something grotesque and unwearable. Then came the fast food: Hamburger and French Fries (1962–63), enormous, mocking, and slathered in gaudy paint. Everything was for sale (and prices started at $21.79). At the center of the display was a cash register, painted to look like a crumpled Jackson Pollock.

Like Kaprow, Oldenburg felt that the idea of what art was, needed to be entirely re-evaluated post-Pollock and abstract expressionism. He wanted to move art out from the four edges of the canvas and into physical space, he wanted it pushed beyond the gallery-museum system and onto the streets. As he wrote in his 1961 essay (one of my favorite pieces of art theory), I am for an art…

“I am for art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum… I am for the art out of a doggy’s mouth, falling five stories from the roof…I am for art you can sit on. I am for art you can pick your nose with or stub your toes on… I am for the art that grows in a pot, that comes down out of the skies at night, like lightning, that hides in the clouds and growls. I am for art that is flipped on and off with a switch.”

It was a raucous, poetic declaration championing the ordinary, the vulgar, and the absurd—embracing everything from smoke and shadows to ear wax and washing machines—as legitimate material for art and was in defiant opposition to the highbrow ideals of artistic purity (hello abstract expressionists!) in favor at the time.

Many of Oldenburg’s oversized food sculptures (Floor Cake, Floor Burger, Floor Cone), were soft and malleable (and were created for a reconstruction of The Store at Green Gallery in 1962). His wife, Patty Mucha, sewed and stuffed the objects, which Oldenburg then painted. By blending sculpture and painting—an uncommon combination—he created interactive artworks that could be squeezed and pushed around the floor. Crucially, these “products” were stripped of all function, existing in form alone.

The Store not only critiqued America’s growing culture of mass consumption in the late 1950s but also took aim at the commodification of art itself. Oldenburg’s work broke free from the gallery-dealer system, offering a sarcastic commentary on how art was sold. The pieces sparked controversy—when the Art Gallery of Ontario sought to acquire Floor Burger in 1967, student protests erupted, and a nine-foot ketchup bottle was created as a symbol of revolt. Rumors circulated that Oldenburg had to pretend the pickle atop the burger was a travel pillow to get it past airport security. And that same year, artist Vija Sturtevant recreated The Store from memory just blocks away, as a post-modernist artistic commentary of her own. She invited Oldenburg to the opening and he attended; however, supposedly after that, he never interacted with Sturtevant again.

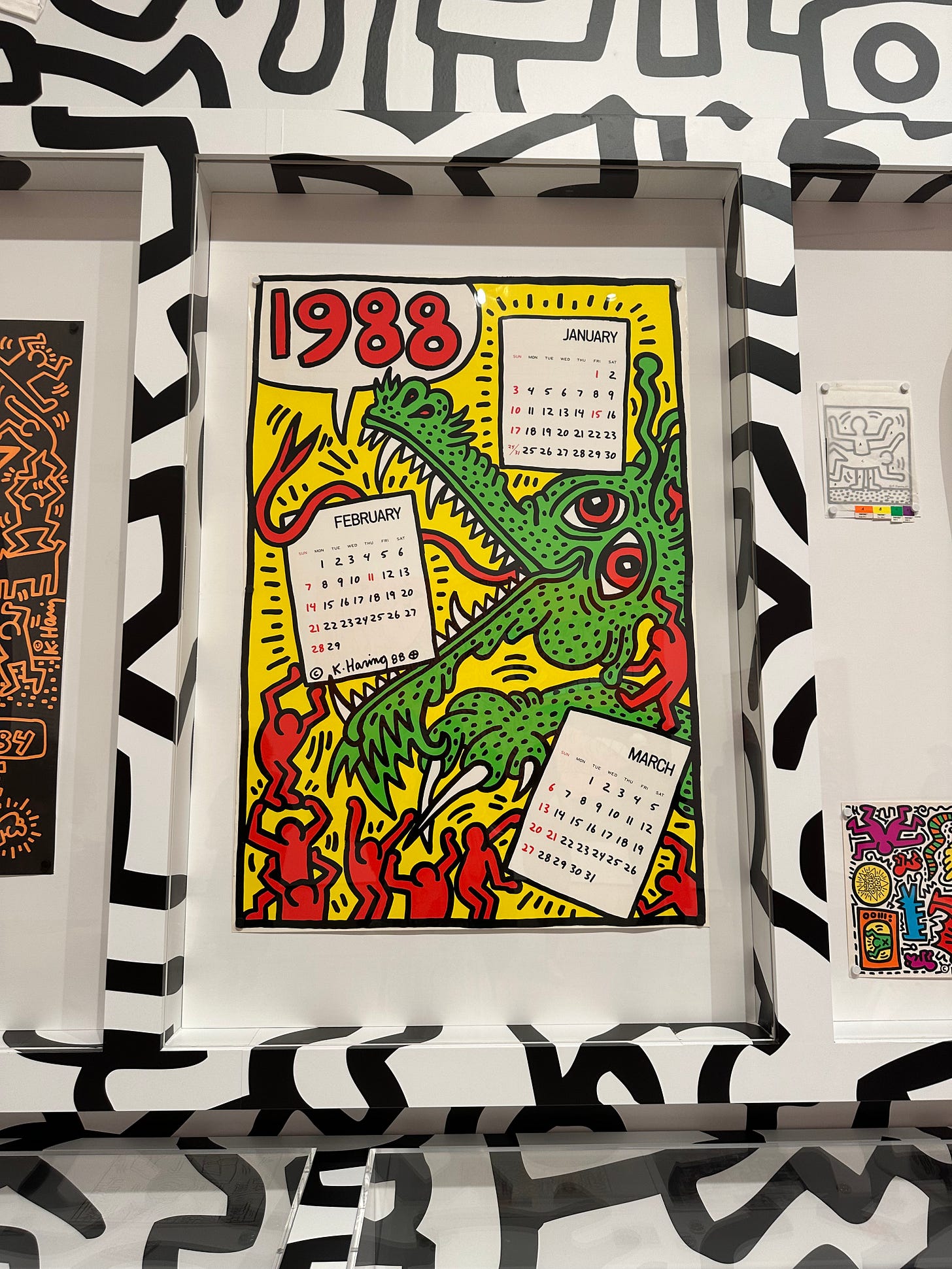

Keith Haring’s Pop Shop

Now it’s the late ‘80s and you’re a few blocks west, walking through SoHo where the once-industrial neighborhood is in the midst of transformation. The air hums with a mix of creativity and urban decay—lofts and galleries now coexist with old warehouses. As you walk past artists’ studios and rundown buildings, a brightly colored storefront catches your eye. It’s Keith Haring’s Pop Shop, a vibrant, merchandise-filled space and it’s taking the spirit of Pop Art into unchartered territory.

Launched in 1986, the Pop Shop sat at the intersection of Haring’s graffiti-inspired art and commercial consumer culture. The store, filled with t-shirts, posters, and other products adorned with his signature dancing figures and bold patterns, blurred the line between fine art and mass-produced goods, much like Oldenburg’s The Store had done two decades earlier.

Haring, who started his career creating public art—graffiti in the subway system—had long resisted the commercialization of his work and believed strongly in art being for the masses. By 1984, however, his subway drawing strategy (he’d draw in chalk over empty subway panels while waiting for trains or on his way to work) was starting to backfire. Mere hours after he’d created them, people were finding, stealing, and selling the drawings for inordinate sums of money. This was antithetical to his belief that art should be for everyone.

So, in response, Haring created the Pop Shop.

“Here’s the philosophy behind the Pop Shop: I wanted to continue this same sort of communication as with the subway drawings. I wanted to attract the same wide range of people, and I wanted it to be a place where, yes, not only collectors could come, but also kids from the Bronx.”

Just as Oldenburg’s The Store questioned art’s role as a commodity, Haring’s Pop Shop pushed the envelope of who art should be for. But while Oldenburg’s soft sculptures offered a satire of consumerism, Haring’s approach was more overtly commercial, allowing his artwork to exist on shirts and mugs—things people could wear, use, and take home.

Lucy Sparrow’s 8 ‘Till Late

Fast forward to 2017, and you’re yet further west, swinging your Gucci Dionysus bag over to the Meatpacking District (RH hasn’t yet popped up in the old Pastis spot, but you can sadly sense it coming). Lucy Sparrow’s “8 ‘Till Late” is an all-felt Bodega at The Standard Hotel whose 9,000 items—Pringles, Frosted Flakes, deli meats, medicine, Ritz crackers, Snapples—are in fact plush, hand-sewn replicas. The store looks like any ordinary bodega, but upon closer inspection, each item is a tactile, meticulously crafted work of art. Once again, every piece is for sale.

While Haring sought to make his art accessible in the 1980s, Sparrow’s felted grocery store spoke to the nostalgia of the handmade and encouraged viewers to touch, hold, and interact with the items for sale. (Sparrow has said she makes her felted produce while watching Netflix and times herself—"1 hour: Pretzels. 1 hour: Bananas.”) The multiplicity of her offerings, attention to detail, and life-like convenience store layout took the store-as-art concept a step further. (The installation closed early when, due to its popularity, she sold out of goods.) Her bodega of stuffed, squidgy items was also a full circle back to Oldenburg’s soft sculptures and the elevation of the everyday into something sublimely surreal. 🥯

Really enjoyed learning about this history of 3-D art/craft.

That’s exactly how I feel about “The Umbrella!” Sounds like a great concept for a book.