Welcome to art Snacks, a newsletter serving bite-sized art history morsels to hungry adults.

I was going to write Issue 1 about the brilliant Sarah Lucas, Turner Prize winner and member of the Young British Artists movement of the 1990s, whose iconic self-portrait is a photograph of her reclining in a chair placed on a checkerboard floor. She’s wearing jeans and a tee shirt with two greasy fried eggs balanced strategically across her chest. It was going to be set against the backdrop of Oasis and The Verve, and Kate Moss wearing those burgundy suede Adidas Gazelles. I even went to the SF MOMA library where their staff kindly allowed me to spend a day researching Lucas, poring over their glossy artbooks in the underground reading room.

But then the atmospheric river came to San Francisco. The Transamerica Pyramid, Alcatraz, the Golden Gate disappeared beneath thick, low-lying clouds that steamed in from the Pacific. It rained, day and night, for weeks straight. Who could dream of wearing suede Gazelles while rainwater, leaves and clumps of jasmine blossoms gushed down the hillside around our home? I fell asleep listening to the drumming of the rain on the roof, I woke up and it was still drumming.

San Francisco during the rainy season is mystical, magnetic, melodramatic. Whitecaps froth the bay. Streetlights shimmer through the fog, a relay league of beacons dotted across the neighboring hills. If you venture out for a nightcap (martini, dirty), you likely end up next to a misted window, or beneath a fading Jefferson Airplane concert bill in the glowy warmth of some beatnik haunt, like Vesuvio Cafe.

And so, I thought about Joan Brown—painter, swimmer, San Franciscan—who said about the city in 1975, “there is this damn psychic energy I’ve talked about that has to do with this place and this body of water,” and I realized what I really wanted to write about was her. And the period of her career I really wanted to focus on, was her SF Bay swimming years during the 1970s. A period during which Brown’s succession of frigid open-water crossings through the shark-infested waters of San Francisco Bay (one of which nearly ended in disaster), led to a series of remarkable swim-related paintings.

Joan Brown (1930 - 1990) grew up in San Francisco. In the late 1950s she enrolled at the (recently closed) San Francisco Art Institute where her tutor, Elmer Bischoff, encouraged her to find the magic in the mundane; to find inspiration in everyday objects: a refridgerator, her bull terrier, her son dressed as a leopard for halloween, or quotidien activities: women bathing, a child eating at a kitchen table strewn with raw veggies, fresh from the market.

Brown’s early works were abstracted, marked by a heavily impastoed painting style, thick swipes of gloopy paint, forming peaks along the canvas. A recurring topic in her works from this period is that of the bather; a precursor to her great swimming paintings.

Depicting bathers/bathing is a centuries old art-historical theme—usually showing a woman, Diana (see above: Titian’s Diana & Actaeon), Susanna (see above: Rembrandt’s Susanna & The Elders) or unsuspecting women in general(!) (see above: Gaugin’s The Bathers), portrayed unawares in the act of washing, through the male artists’ gaze. Those women are posing, stylized, vulnerable. Their bodies aspire to represent the ‘perfect’ female form (a way for artists to show off their life skills) and are made into either symbols of virtue or wicked immorality. Largely all these ladies are subjects of acute voyeurism.

But Brown upends this theme. In Girls in the Surf with Moon Casting a Shadow (below), two women stride through the shallows emerging from an outdoor night-swim. They don swimming caps, conveying their seriousness in this endeavor. Their naturalistic bodies are pink and pricked with gooseflesh from the bracing cold. At the image’s center, a forceful V: these intrepid ladies have interlocked hands, they are in solidarity against the raw, unpredictable power of the ocean that swills around them. There is a matter-of-factness about this painting. We are not creepily onlooking, this is simply a thing that is happening and Brown is reporting that to us.

By the early 1960s Brown was exhibiting in New York and MOMA had acquired her work. But by the mid-late 1960s, she was questioning her ‘heavy expressionistic’ style to the dismay of her NY dealer (remember the NY art scene at the time was all about abstraction or Pop Art). She parted ways with her dealer (a brave move!), and back in the the protective, foggy cocoon of SF spent several years freely experimenting with her style: thus leading us back to the rain, and the mist, the frothy bay. San Francisco’s wet, psychic energy. When she emerged, her style was figurative and lucid: clean lines and bright colors.

In 1969, Brown and her then husband, Gordon Cook, moved to Rio Vista on the California Delta. The Delta is the largest estuary on the Pacific Coast, the meeting point of the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers; a labyrinth of interlacing waterways snaking for 1,100 miles through marsh and farmland. The waterways are dotted with islands (and in turn with homes, houseboats and bars) many of which are accessible only by boat.

In Rio Vista, Brown converted a barn on her property into a studio, and when she wasn’t painting, started to re-explore her love of swimming (indoor and outdoor), entering swim races and local competitions. Encouraged by Cook, a member of the Dolphin Club— an open water swimming and rowing club near Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco—Brown frequently made the long drive along the Delta to the city to swim in the Bay. At first she swam laps in Aquatic Cove—a sheltered cove open to the Bay—but as her confidence grew, and with support (she enlisted the aid of Charlie Sava, International Hall of Fame swimming coach) she ventured into the open waters.

San Francisco Bay is known for its forceful currents. Swimmers of differing speeds must take divergent courses through the water to account for the deviation caused by these currents, ‘sighting’ their personal ‘landmarks’ every few strokes and swimming towards them rather than blindly following the person ahead through the water. These landmarks—The Bay Bridge, TransAmerica, Coit Tower—soon made it into the backgrounds of Brown’s works. But what was happening in the foreground?

Brown’s great preoccupation at the time: the Alcatraz crossing.

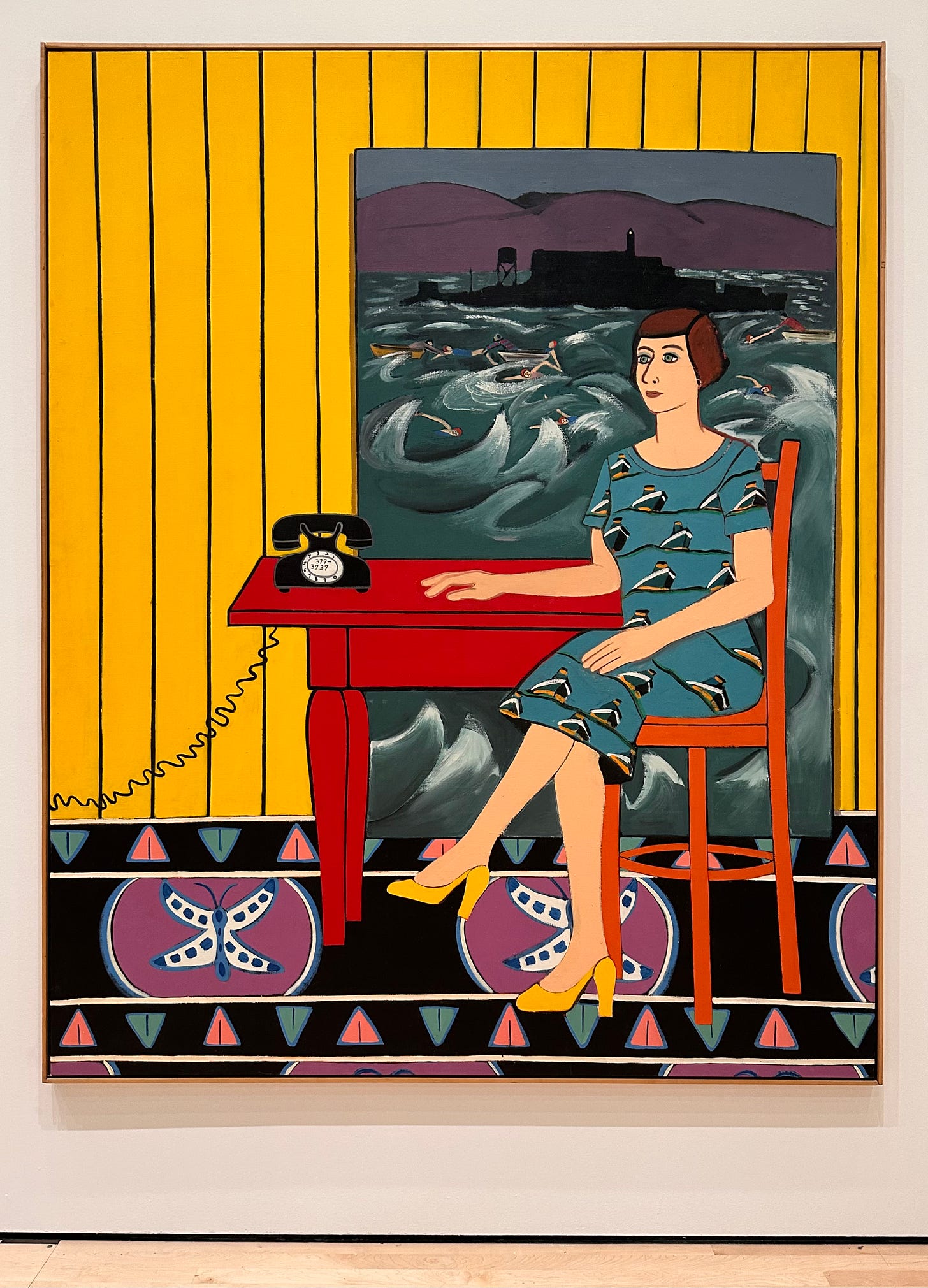

The Night Before the Alcatraz Swim (above) is my favorite work by Brown. When I saw it in person at SF MOMA’s Brown retrospective last year, it towered above me at 7 feet tall, its orange, blue and purple hues—the devastating colors of the aftermath of a nuclear disaster—radiating outward.

Encountering this painting makes you gasp. If you’re a Bay area local maybe it’s the recognition of that dusty, purple, sunset view of Alcatraz, so simply color-blocked yet frighteningly accurate. Perhaps it’s the haunting blip of the lighthouse, stalwart against the thrashing waters. Maybe you feel empathy with Brown’s exhaustion (this is a self-portrait) or dread or anxious anticipation as she warms up post practice, the night before the event: hair wet, coffee steaming. Or, perhaps it’s the way Brown conveys the Dolphin Club’s walls with their almost crazy-making knotted-wood paneling. When I look at this picture, I hear Grace Slick’s (Jefferson Airplane’s) White Rabbit, that surreal, hallucinogenic, marching crescendo into some wild, unknowable, deeply alluring place, which for Joan was the dangerous Bay.

The particular Swim that Brown is contemplating in The Night Before the Alcatraz Swim was the first all-women’s Alcatraz crossing in August 1975. It ended in near-fatal disaster. The women were taken out on boats and deposited in the water close to Alcatraz. They then had to swim back to shore, navigating fierce currents and… shipping lanes.

During their passage, an immense freighter barreled through their course, creating a massive wake and thirteen-foot waves: impossible swimming conditions. Brown and sixteen other women nearly drowned and had to be pulled from the water. The women were exhausted, disorientated and hypothermic after the ordeal. Understandably, this near-death experience hung heavy on Brown’s mind.

After the Alcatraz Swim #3 (above) was painted after this incident. We see Brown ensconsed within a warm, safe space. Her hand is within stretching distance of a phone (to call for help if she needs), the phone is wired (grounded) to the building, solidly tethered to land. Her clothes: heels and a fitted dress printed with an image of the freighter—are items of land-wear only. All of this contrasts with the painting within a painting behind her portraying a more complex inner state. There we see churning waters, strong waves and swimmers in various states of distress: some swim into the belly of waves, others are being hoisted into rescue boats. The swimmers flail in every direction; the ominous black rock, Alcatraz, looks silently on.

Brown has said that she “couldn’t say all I wanted to say [on this theme] in one painting.” Painting about this incident became a way to reckon with what had happened. She knew she was going to attempt the swim again, so perhaps ‘painting it out’ was a way of metabolizing her fear and readying her mind for her next attempt. She created numerous works on the theme.

After the Alcatraz Swim #1 (below), has the same comforting interior, but the painting within the painting conveys a more alarming inner state: a sole swimmer grappling sans backup in desolate but vicious waters. It is night-time making the scene all the more horrifying.

This incident was an experiential black mark on an otherwise positive and joyful swimming career. Brown made many other swimming-related works, many much more celebratory, and I encourage you to check them out. (The Bicentennial Swimming Champion and The Swimmers #2 are especially evocative. Stumbling upon the latter was my first encounter with Brown’s work. Some years ago I was leafing through an interior design monograph where I saw it hanging on the wall of a sublime Hamptons living room!)

Brown went on to complete the crossing. She also, along with five other lady swimmers, successfully sued the string of male-only outdoor swimming clubs (the Ariel, Dolphin and South End Rowing Clubs) resulting in them finally accepting female members.

Additionally, Charlie Sava helped Brown cut her swim time in half. Her relationship with him left an indelible impression. She implemented many of his ideas about teaching in her own role teaching at various Bay Area institutions, including during her 16+ year stint at Berkeley. Sava inspired numerous works including: Self Portrait with Swimming Coach Charlie Sava, 1974; and Charlie Sava + Friends (Rembrandt + Goya), 1973. Images from his instructional book on swimming, inspired a series of 3-D works, like Divers, 1974, below.

The next chapters of Brown’s life were equally remarkable and are worthy of being art Snacks of their own. They included travels to South America, Eygpt and India. Increasingly enthralled by Eastern mysticism, Brown created large, colorful works depicting Hindu deities, Eygyptian tombs and mythological paintings filled with animals (see Year of the Tiger, 1984, at the top of this letter).

Brown was a mother, a painter, an instructor, a swimming champion, a smoker, a proud San Francisan, a spiritual devotee. She hosted chicken dinners to celebrate friends (served on commemorative ceramic plates she made herself) and got married in a Hindu ceremony (to her fourth husband) in SF MOMA!

Tragically, Joan Brown died in India when a column collapsed on her as she was helping erect a sculpture she’d created for her guru. She was only 52.

If you want to dive further into Joan Brown’s legacy try:

this gorgeous VHS archival interview with her

scroll this tumblr showing key images from her estate

listen to Jefferson Airplane’s iconic album Surrealistic Pillow to get in the mystical SF mood or…

book a night tour of Alcatraz (highly recommend).

And if you’re up for a nail-biting movie about open-water swimming, watch Netflix’s NYAD about Diana Nyad’s attempts to be the first person to swim from Cuba to Florida.

I hope this gave you something to chew on during West Coast rainy season! The photos aren’t perfect because they’re all iphone snapshots that I’ve pulled from my personal digital art journal (think of it as that blurry photo of the cheesy pasta dish you took at dinner to remember its incandescence), but I hope they convey the gist! Serena x