Welcome to art Snacks, a newsletter serving bite-sized art history morsels to hungry adults.

It’s a balmy summer morning in 1966 when you disembark your water taxi near the Giardini for the Venice Biennale. As you stroll along the white gravel paths between the national pavilions, you’re still buzzing from that second Bellini at Harry’s Bar. Peggy Guggenheim might be somewhere close by in giant sunglasses, or perhaps you catch a fleeting glimpse of one of her scampering dachshunds.

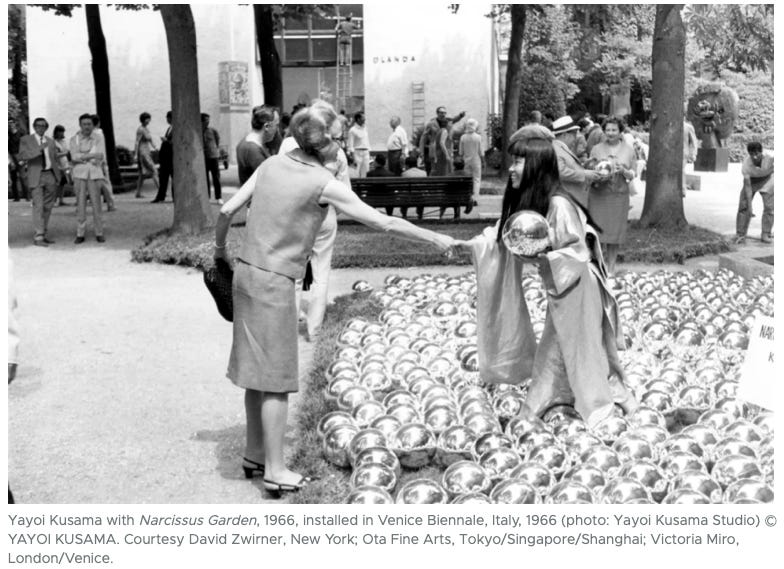

And then, turning a corner outside the Italian pavilion, you stop. Before you is a sea of 1,500 mirrored spheres gleaming in the grass. A woman in a gold kimono hovers among them, next to a handwritten sign: “Your Narcissism for Sale.” She’s selling the orbs for $2 a piece.

This was Narcissus Garden, and it was not on the official program. Long before Instagram made selfie-reflection a performance, Yayoi Kusama held up her own mirror to the art world, confronting its ego, commercialism and hypocrisy.

When Kusama (born 1929) first traveled to America in 1957, her aeroplane cabin “was empty except for two American GIs, a war bride and [her].” Because there were limits on how much foreign currency could be brought into the country, she packed her suitcase with sixty silk kimonos and 2,000 of her drawings and paintings that she could sell to survive. It had taken her eight years to convince her mother to let her leave Japan during which time she’d initiated a correspondance with her artistic hero, Georgia O’Keeffe seeking advice on how to make the transition to the U.S. (Kusama took a train from Matsumoto to Tokyo to look up O’Keeffe’s address at the American Embassy, then wrote to her asking for any advice for a budding artist who was determined to see America.)

Kusama soon settled in a dilapidated downtown Manhattan studio with broken windows and a single blanket. She ate improvised dinners - handfuls of chestnuts, or discarded cabbage leaves stewed with fish heads in makeshift pots. However, each day she started work before first light and continued long past sunset, toiling on paintings, including those for her first show, Obsessional Monochrome, 1959, which showcased a series of five white-on-black infinity net paintings (where using acrylic she applied thousands of looping, scoopy brushstrokes in a net-like pattern across an infinite-seeming canvas field). As she explains in her autobiography,

“I often suffered episodes of severe neurosis. I would cover a canvas with nets, then continue painting them on the table, on the floor, and finally on my own body. As I repeated this process over and over again, the nets began to expand to infinity. I forgot about myself as they enveloped me, clinging to my arms and legs and clothes and filling the entire room.”

The show was held at the 10th Street Brata Gallery where the artist and critic, Donald Judd, came to view her work. Judd was one of Kusama’s first close friends in the art world and was the first to buy a piece in the exhibition. The exhibition was well-reviewed, and the gallery was packed with attendees thronging to see her mesmerizing 14+ foot canvases. All her paintings sold. So began Kusama’s ascent within the New York 1960s avant-garde scene.

Like Kaprow and Oldenberg, Kusama strove to break out from the strangle-hold that action painting and abstract expressionism held over the NY art scene at the time. In a studio in the same building as Judd’s, she started working on her phallic soft sculptures which she called Accumulations. Using fabric, stuffing, and sewing techniques traditionally associated with domestic craft, she obsessively covered household objects—chairs, shoes, boats, suitcases—with hundreds of hand-sewn, protruberances.

Kusama’s preoccupation with these forms was rooted in childhood trauma and sexual anxiety, which she channeled into visual critiques of desire, patriarchy, and the repression of female psychological experience. The repetition of the forms—endless, obsessive, uncontrolled—also links them to her broader project of self-obliteration, where the boundary between and sensitivity to body, object, and environment begins to blur. (You can read a beautiful piece about these soft sculptures here).

Narcissus Garden in Venice was born directly from Kusama’s interest in infinite repetition and the sublimation of the self through endless iteration. Just as her ubiquitous phallic soft sculptures served to eviscerate her childhood sexual trauma, the mirrored ball sought to dissolve the boundary between the self and the environment: a way to deconstruct the ego.

The “Your Narcissism for Sale” sign was strategic: its confrontational and subversive tone was designed to grab the art world’s attention. And, as with Oldenberg’s Store, selling the spheres for $2 apiece was a pointed commentary on the commercialism of the art world.

It also presented a paradox: performance art definitionally resides outside of the gallery-dealer system (it’s ephemeral), yet here Kusama was intentionally monetizing it.

Narcissus Garden has been restaged across decades and locations. In one restaging with MOMA PS1, the garden was reconstructed within a dilapidated warehouse in a former military site, Fort Tilden, situated on a barrier island at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. I saw it in 2018 and it was impossible not to link the work to the devastation caused by Hurricane Sandy that had ravaged the surrounding area some years earlier.

In another version at the Rubell Museum (below), Kusama’s balls have been placed within one of her infinity mirror rooms, extending the ball ad infinitum. For me, it was only during this viewing that I understood one of the central truths of the work. Not only could I see my reflection in any individual ball, but I could see it in every ball of the sea of infinite balls. And it was then that my reflection entirely lost its meaning (Kusama’s concept of self-obliteration).

Narcissus Garden at the 33rd Biennale presaged an important and often unmentioned body of performance art work for Kusama during the late 60s: her ‘Body Festivals.’

In one, entitled Anti-War Naked Happening (1968), Kusama orchestrated a demonstration on the Brooklyn Bridge where four naked people covered in painted polka dots, brandished a banner saying, “SELF-OBLITERATION.” Kusama later explained that she wanted to highlight the “tragedy of sending young people to die in Vietnam” by contrasting it with the beauty of unclothed human bodies.

In another unsanctioned festival, Grand Orgy To Awaken the Dead (1969), Kusama invited participants to strip naked in the outdoor sculpture garden at MOMA and “embrace each other while playfully engaging the sculptures around them” (per MOMA). For Kusama, the artists exhibited in the garden were all fusty and dead (Maillol, Giacometti, etc). Kusama was highlighting the need for the museum to place greater focus on contemporary artists. The happening made the cover of the Daily News with the caption, “Impromptu nude-in was conception of Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama. Crowd takes it in stride. (Some took strides to get closer.)”

And, in late 1968, Kusama sent seductive invitation to Richard Nixon (“An Open Letter to my Hero, Richard M. Nixon” (1968)) in an attempt to coax him into ending the war.

Today, Kusama lives in a psychiatric care facility in Tokyo. She checked herself in decades ago, and from there, every day, she walks to her nearby studio to work. It’s a self-chosen balance between solitude and compulsion.

The art hasn’t stopped. For Kusama, the world itself is made of polka dots. They’re not just her aesthetic but her cosmology too. “Our earth is only one polka dot among a million stars in the cosmos,” she once wrote. “Polka dots are a way to infinity.” 🪩

P.S. A lot of people reading this are new this week. If you’re wondering who the heck I am, you can find out here. If you want to know what’s going on, we are currently on a magical mystery tour of the 1960s New York avant-garde art scene. My post on Allan Kaprow, who coined the ‘Happening’ and encouraged women to lick jam off windscreens, can be found here. You probably read my follow-up post on Claes Oldenburg, here. Kusama was also in their scene, albeit taking her artistic practice in a very different direction (hence this post). And, if you want to learn more about the Venice Biennale and my recent trip to it, you can do that here. If you like the Venice post or this one on Hernan Bas (more images, less text) please do drop me a note in the comments!

Given that we ran through the Biennale Garden this morning - this was the perfect pre-read.